Here's the text of the talk I gave at the Flying Blind symposium on Thursday 3rd December:

The only way I can think of to try to understand a paradigm shift when you're in the middle of one is to look for previous examples.

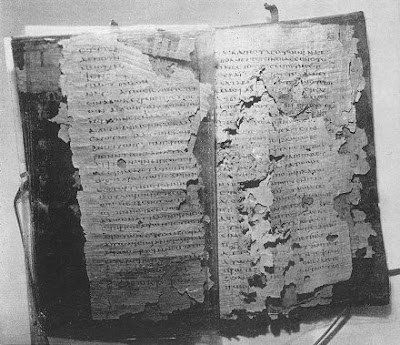

It's important to remember that earlier technologies have a tendency to leave fossilised remnants of themselves preserved inside the new one. Take the shift from scroll to book in late antiquity, for instance. Scrolls are hard to store and very limited in length. The book-divisions in Homeric epics, for instance, tell us how many scrolls it took to write out each poem: 24.

Hollywood movies have accustomed us to see them as continuous strips of print, unrolled vertically like a teleprompter. In fact they were generally read horizontally, with a series of columns unfolding across the exposed area. It was no great stretch to transfer this idea of columns of writing into the idea of separate pages in a book. Sewing or gluing pages into a book (or a codex, to use the technical term) is, however, extremely labour-intensive, and there was therefore a long period of overlap when the two co-existed.

We talk about internet pages, and we speak of scrolling down them. In other words, our ways of thinking about writing in the new medium are still imagined in terms of the technologies familiar to us. We still prefer reading down rather than across - the idea of linking computer screens to make a larger display area should probably be seen as more analogous to fold-out pages in an illustrated book than to any real re-imagination of the medium.

Page design and layout, fonts, chapters and titles, these all come with us as we attempt to transfer our means of expression into the electronic media. At present, in fact, given the tendency of electronic storage systems to decay or become obsolete within a few decades (or even a few years) - also given our lessened attention spans in front of a screen - the technology of the internet actually has more analogies with that of the scroll than that of the book.

Cross-referencing and footnoting is definitely easier on webpages, though. The idea of hypertext, of point and click, while still clearly a development of the concept of indexing, will undoubtedly revolutionise our ways of thinking about information-transfer over time.

I guess the easiest way to talk about my own thinking and responses to the challenges of this new medium is to refer to the experiments I've made to date in how to construct literary texts - and, especially, narratives - in a way that makes some use of its innovations.

My first novel, Nights with Giordano Bruno (Wellington: Bumper Books, 2000), is a meditation on the physical possibilities of the book, or rather, the idea of a single page within a book. It consists of a number of discontinuous texts, scattered throughout according to a set of numerical formulae. No one page follows on from the page before, but each of the various stories can be followed reasonably easily if you care to search for the next page in the sequence. Alternatively, you can read it straight through as a kind of textual mosaic.

When I decided to try and transfer my book to the internet in 2007, I was forced to regard the pages as individual computer pages, hyperlinked to a table of contents which enabled them to be regrouped into their constituent stories. The ease with which this could be accomplished online, though, negated some of the resistance to rearrangement characteristic of the book. My Bruno website, then, while it physically copies the book's text and internal arrangements, could not be said to do the same for the initial reasoning behind that arrangement.

My next novel, The Imaginary Museum of Atlantis (Auckland: Titus Books, 2006), again tried to play with the physical form of a book in what I then saw as innovative ways. Again I used the idea of the individual page, but this time I arranged the text as two separate but intersecting sequences, an alphabetical encyclopedia of Atlantean lore running one way, and a series of automatic writings running in the other direction. Each spread, then, contains two pages different ways up. The reader is forced to decide which way to go when reading it (though, again, it can also be read as a series of mosaics rather than sequentially).

The website I designed for the book attempted to echo this arrangement by arranging the pages on two separate blogs, each hyperlinked and cross-referenced to the other. The physical book already contained a series of putative hyperlinks in the form of footnotes, but of course I was now able to make these "real" hyperlinks, and to join them up in the pre-designed sequences I'd originally had in mind. The book, then, while still primary, has been in some ways re-imagined in its new incarnation. They complement each other, rather than simply echoing each other's form.

The third novel in what I'd now taken to calling my trilogy (the R.E.M. - or "Random Excess Memory" - trilogy), EMO (Auckland: Titus Books, 2008), was based around the idea of crossing the page. Before the advent of cheap, acid-based paper in the mid to late nineteenth century, it was quite common for people writing letters to write vertically down the page, and then turn it round and write the other way, horizontally. Correspondents became quite adept at deciphering such texts, and I wondered if it would be possible to do something analogous on the pages of a book. Could one have, in fact, a literal subtext to the master narrative marching down the page?

The interesting thing to me about this experiment is that it was dictated by my decision to try and compose an internet novel, rather than the other way round. The electronic version of the text preceded its physical manifestation. I wrote a series of texts in the form of separate blogs (I'm addicted to blogs - as you may have noticed - for their cheapness, their easy accessibility, but also, somewhat paradoxically, for their technical limitations. They focus one's mind on the simple problems of textual transmission in a way that a more flexible platform might not). I then hyperlinked my fictional texts to other, "underlying" texts in the hopes of setting up a kind of double-focus in the reader's mind.

My latest experiment has, however, moved away from simply presenting chapters of fictional prose as online pages. Instead I've decided to try and tell a story through pre-existing textual paradigms, specifically online course outlines and lecture notes, a kind of information I've spent a good deal of time working on as part of my job (here's an example: the website for my stage three course in Travel Writing).

I therefore wrote and compiled two fictional course-outlines, Banned Books & Crisis Diaries: each complete with reading lists, lecture schedules, and assignment outlines. The novella I ended up writing (due out from Titus Books next year as part of a larger volume of short fiction) masqueraded as a folder of notes compiled by the teacher of these two courses.

It's titled, accordingly, Coursebook found in a Warzone, and is set in a slightly future version of right here. The putative author of the texts in this folder may have been killed by a sniper, or he may simply have lost his briefcase while crossing the war-torn city (I imagine it a little like 80s Beirut or 90s Sarajevo ... or perhaps modern Baghdad). In any case, the story comes to an abrupt stop. That's one of the reasons that it's subtitled "A Whodunit." There are numerous hints throughout at the author's guilt - or at any rate complicity - in certain crimes. Unusually for the detective genre, though, the crime may be harder to identify here than the culprit.

I think the advantage of this new twist on the internet-as-writing-medium is that it makes use of the kinds of texts which already exist online. Readers of my novella can easily consult the course outlines online, but that won't necessarily help them in understanding the nature of the story. Just as Samuel Richardson in the eighteenth century first wrote a set of letters as an educational primer to polite discourse, then, captivated by the possibilities of the form, composed the world's first epistolary novel, I think it's more interesting to adapt aspects of one's writing to the dictates of the new medium than simply to use it as a mirror of the old.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

1 comment:

hello... hapi blogging... have a nice day! just visiting here....

Post a Comment